Face-to-Face: The Curious Case of Soumitra Chatterjee Making Portraits

Sovan Tarafder

None of the faces is ever familiar to me. Usually they are fairly still, but they are not static images; they are alive... They are clearly not aware of my watching them. Yet I am able to make them look at me.

John Berger (And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos)

In his autobiographical journal serialised in a Bengali daily, Soumitra Chatterjee (hereafter Chatterjee) took the reader to some hidden chambers of his psyche. Out of a plethora of reflections on various topics that intrigued him at different points of time, three threads, cognate and illuminating, would be called here in this essay. Chatterjee revealed that he deeply enjoyed drawing human faces. Chatterjee stated that as an actor, he would always follow the facial cartography of persons around him. Also, Chatterjee informed that visualizing the face of the character he would be playing in a film/play is the first step to his actorial preparations for the same. The present essay is going to be built around these three pieces of information, placing them against the backdrop of a few strands of thoughts on the cultural economy of faciality. Being the collaborator of the journal mentioned above, the present author had the privilege of conversing with the late maestro, among other things, on this particular topic. A few reactions elicited thereof would introduce the core argument which is going to be explored further in the later part of this essay.

How Chatterjee externalizes his reflections on the interconnectivity between addressing a role and making a portrait (of a face) is interesting:

‘I’ve often come across a question: why do I keep drawing faces? Whose faces are they? For an answer, all I can humbly offer is, this is something maybe even I myself am not fully aware of. Tracing the originary sources of the stream of images that I remain flooded with is beyond my capability. Also, the way a painter engages with the stream of image is so very different from the way I do. One would not be compatible with the other. Whenever I think of a face, I actually think of the entire character, which gets reflected in the mirror that I call a face. It captures the inner details of the characters. It captures the respective ways they look. Their ways of looking bring out the light within, often the darkness and at times the grey zones that they inhabit. (Chatterjee, 2020: 37-8; translation mine)

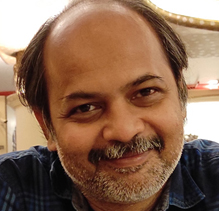

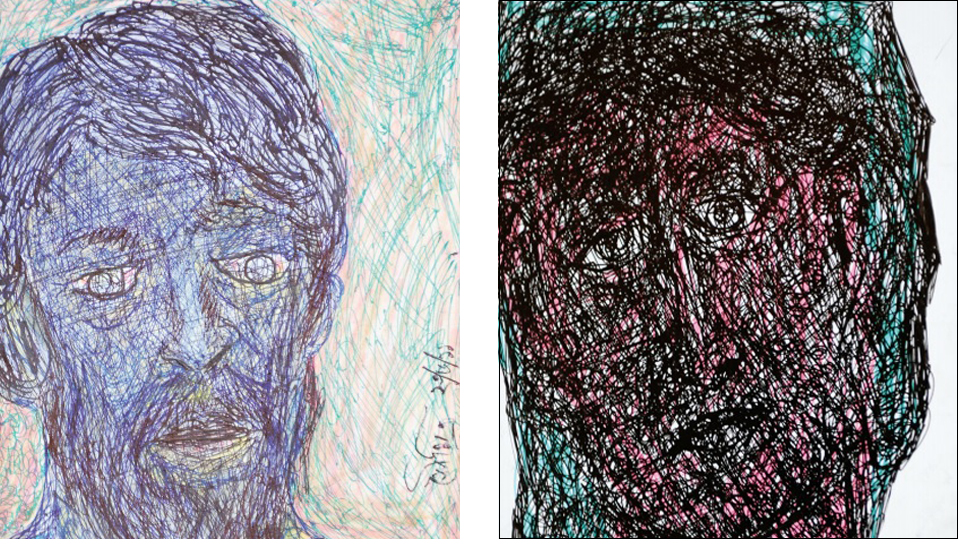

Chatterjee clearly states that the way he engages with these portraits is different from being just painterly. One who gazes at and explores the face(s) is the actor (in him) who then lets the painter (in him) draw them. It is the gaze into the face(s) that sets off his actorial journey driving him deeper into the nooks and crannies of the character(s). However, converting the probing gaze of an actor into a meaningful painting does require a different sort of skill-set. The inner vision needs to be complemented with some sort of formal training in art, which, as is known, Chatterjee did not have any. Accordingly, his figure-drawing evinces his uncertainty and lack of formal knowledge in anatomical drawing. However, when it comes to the face, Chatterjee performs way lot better, rather uncannily, given his lack of knowledge in the fundamentals of figure-drawing.

Quite expectedly, he does not go for the figural verisimilitude. Instead, the faces are visibly impressionistic, since for him the act of painting a face essentially follows the act of gazing at and thereby absorbing the kernel of that countenance. How the actorial self configures this inner dynamic has nicely been explained by Chatterjee himself.

‘I don’t know really how, but yes, while drawing faces, I find the flow of lines easier to handle. And, the faces become expressive too. Actually, for me the face is a rather familiar terrain. I know the map of muscles. Twitching which one, and how much, would get the desired result is something I’ve been watching since the inception of my acting career’, Chatterjee uncovered the performative secrets in a personal chat with the present author, ‘How the eyes can tell the story without even a word being uttered has been a part of my practising regimen since long. Also, engaging regularly with camera and the live audience on stage requires me to be even more conscious of my face. Cinema has a privilege that stage doesn’t offer. Getting very close to the actor. So, when it comes to facial acting you need to be very cautious. You just need to know every tiny part of your face. Maybe that’s the reason why I find faces easier to manage while painting.’

Interestingly, the face is what inaugurates his process of reflecting on a certain character and eventually, he treats the face as the microcosm of that character. So, it is the take-off point that in a sense turns out to be the destination of the very same journey. Chatterjee throws some interesting light on the process in his journal:

‘What I reckon as the character is its unique identity. Something that distinguishes it, sets it apart from the rest. This uniqueness is at times very pronounced, and at times implicit, not easy to locate…Hence, the actor needs to be a highly attentive watcher. He keeps on watching, follows the nuances and analyses, as he wants, whatever visits his watchful eye. Neither in a very formulaic way nor in ways necessarily radical, but the actor in his own method keeps on following the causal relations that go on to build up the character from within…As the proverb asserts, face is the mirror that reflects the mind. But, the measure of that reflection is something that only the actor can calibrate.’ (Chatterjee, 2020: 195-6; translation mine)

Then he directly goes on to reveal the synergy between his performative faculty and his penchant for drawing faces:

‘Face is what triggers the process of constructing a character in my mind. Often I draw an image of that character. I would like to find how he throws a look, how his facial expressions synchronize with the words he utters, how he can express ecstasy or agony simply by his facial organisation.’ (Chatterjee, 2020: 196; translation mine)

An interesting case-in-point is King Lear that was staged in Bengali as ‘Raja Lear’. Chatterjee, an ardent fan of Shakespeare and hugely enthralled with the project, played the eponymous role. The way he visualised the character was captured in a haunting sketch of the king. The play captures the tragic figure both in his royal splendour and also in penury, stripped to nothing but his frail, corporeal figure.

While revisiting those moments in a chat, Chatterjee cast a glance at the infirm glory of the Shakespearean king, his eyes looking a tad lost: ‘I was excited, you know, it’s a dream role that at last came my way. I drew a face of Lear. The old, vulnerable, hapless king, not a patch on what he’d been once. It’s an interesting portrait, of someone I’m emotionally, and aesthetically familiar with, but it’s a fictitious character, so I can’t know his face. None can, for that matter. I’ve seen photos of Sir John Gielgud or Sir Laurence Olivier playing Lear. So for me, those are the faces of Lear. And, then it was my turn to be that face. I drew the mentally deranged state of the king, his eyes awfully blank, yet by being so, expressive. My challenge, as a painter, was to encapsulate the entire tragedy of the person in a single countenance.’

Slipping into a silent, reflective mood, Chatterjee got nostalgic. Not only did he enjoy playing a Shakespearean character, it was a tumultuous phase in his life, too. Almost immediately after having cardiac stent put in his body, he was diagnosed with Cancer. On the verge of completing seven and half decades of his life at that time, Chatterjee somehow could relate to the violent, stormy night that left old, homeless king scathed within. With several ailments threatening to rock the personal world of Chatterjee, the veteran actor seemed to strike a secret chord with the tragic character he later played with élan. The portrait he drew of Lear indicates how proximate to the character he wished to take himself to. The blank gaze wrought on that portraiture is a chasm of nothingness that neither addresses nor returns any look. It is a look-in-itself, a foreclosed gaze that, presumably, shaped Chatterjee’s encounter with the character.

But, why did he draw it? Was it any commonplace painterly drive to make a portrait? Or, was it a step to internalize the features of the character and also to externalize his comments on it? When a celebrated actor appears in an iconic role and draws a portrait of the same, it offers a problematic worth probing further.

How does a face help him visualize a character? In the said journal, Chatterjee has an interesting answer:

‘In fact, whenever I reflect on a character, the first thing I do is to conjure up its face. Maybe the experts in psychology will be in a better position to explain why and how, but this process does work in my case. I only know that face is the door, pushing what I can get to enter the fictional construct that I am supposed to play.’ (Chatterjee, 2020:38; translation mine)

The metaphor of door is especially evocative since it has the dual register of space and time. It not just locates the face, a la door, as the outer and most perceivable part of one’s entity, but goes even beyond such a fixed spatiality. As Chatterjee asserts, the face (of the Other) initiates an inbound journey for the actor. Like a door, the face lets the actor into an unfamiliar structure that invites him to explore it. Exploring a structure, like inhabiting a character, is something that unfolds in space and in time as well. When Chatterjee, as an actor, prepares to perform a certain character, the face of the same is what he seizes as an opportunity to intervene. It is like an opportunity that a door dangles before us. There is a destination that dazzles in its unique incomprehensibility and leaves him with a choice. To go or not to go, that remains the question.

The comparison of the face (of an Other) with a door gestures to a strand of thought enunciated by eminent philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. Positing the thoughts of Chatterjee alongside the broad theorization by Levinas is proposed here only to find if the philosophic threads would, in some ways, add some interesting perspectives to it.

As has been noted in an essay, Levinas has written frequently about door which, for him, is invested with the beckoning of infinity (Alford CF, 2004:150). Also, the door presents one with a choice whether to open or close it. If one seeks to approach a face, he needs to keep the door open. Spatially, this is a movement opposite to what Chatterjee has written in his journal. While Levinas posits the stranger (the face) outside the door and wants the subjectivity within to be receptive enough to let him in, Chatterjee does not assign the stranger this inbound movement, but treats him as an unfamiliar zone with his face being the doorway that leads (the actor) to the interiority of that stranger.

So the theorist and the actor posit the face (the stranger that is) in two different sides of the door, yet they share something that secretly binds them together. It is the agency of the person who faces the stranger. The agency involves the ethico-aesthetic responsibility of not being foreclosed, whichever side of the door he finds himself in. As Levinas has put it,

The "vision" of the face as face is a certain mode of sojourning in a home… no face can be approached with empty hands and closed home…the separated being can close itself up in its egoism, that is in the very accomplishment of its isolation...The possibility for the home to open to the other is as essential to the essence of the home as closed doors and windows. (Levinas, 2007:172-3)

This reflection does not just evince a secret longing for the Other who is on the other side of the door, but more significantly places this act of reaching out as a choice. As a professional actor Chatterjee did not have much option though. His professional commitments made him impersonate different types of characters of which a few, like King Lear, lured him to explore further. To explore his actorial potential vis-à-vis the construction of the character he seeks to engage with.

He felt drawn to those unfamiliar faces, found himself implicated in the conundrums of life those fictional beings were riddled with and these identifications eventually led him to the portraits he drew. Painting the portrait was evidently a part of his preparation for the role, at the core of which remained his intention to engage with the Other.

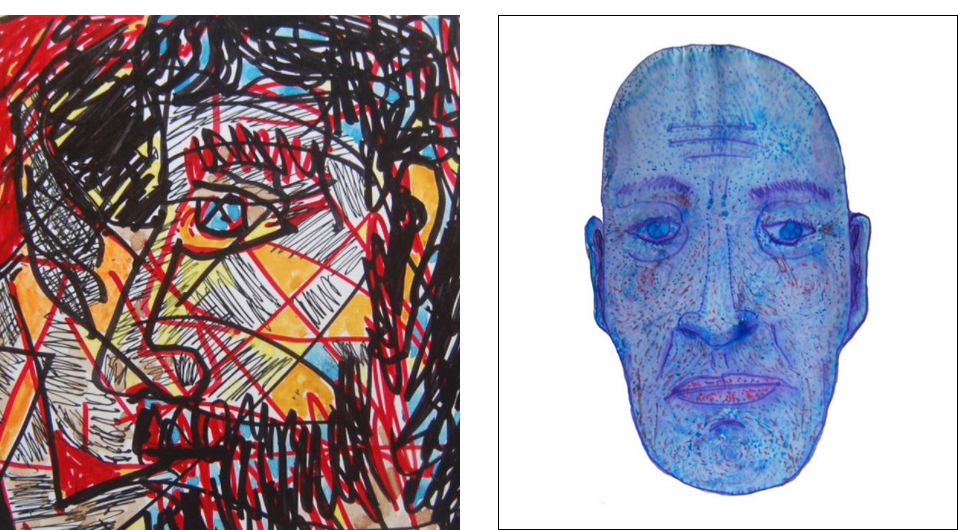

King Lear is a distinguished face Chatterjee made a portrait of and played famously in a stage production, but there are also a lot more who cannot directly be traced back to the list of characters he played. They are anonymous, evade any such distinct familiarity yet each in its own way constructs the otherness that Chatterjee wanted to negotiate with. Mostly these are faces that are disturbing, represent the margin and remain outside the securities of life carefully valorised by the middle class people, the section Chatterjee himself was hailing from.

These portraits are mostly made of chiaroscuro consisting of densely crisscrossing lines, discernibly evoking the faces drawn by Rabindranath Tagore. Chatterjee himself has admitted being inspired by the Tagorean portraits (Chatterjee, 2020:38) His non-trained hand does not make much use of rich tonal variations of colour. Instead, he relies on lines that carve out the portraits through an engaging distribution of light and darkness. The faces that he drew seem to be stemming from an unhappy consciousness, though not in the proper Hegelian sense of the term. In Hegel the unhappy consciousness drives the individual cognitive subject to place himself through his subordination to God, a more powerful entity (Rockmore, 1997). In Chatterjee’s case, the artist (cognitive subject) is the more privileged self. For him the unhappy consciousness, in an inverted form, makes him define himself through his cognition of the less privileged section of the society. In his poems also Chatterjee has often defined himself vis-à-vis the poorer, less powerful section of his fellow citizens. His artworks, even more than his poems, bear the stamp of this societal coordinate. This unhappy consciousness also points to his intent to negotiate with the Other.

Interestingly, while Chatterjee makes the portrait of the Other in order to negotiate with its otherness in a more meaningful way, Levinas has problematized this engagement further. As he points out, encountering the other as a face is to find him in an irreducible otherness from the self. It is a crevasse impossible to negotiate, making the Other utterly incomprehensible and inassimilable. As Levinas writes:

“The face is present in its refusal to be contained. In this sense it cannot be comprehended, that is, encompassed. It is neither seen nor touched – for in visual or tactile sensation the identity of the I envelops the alterity of the object, which becomes precisely a content.”(Levinas, 2007:194)

This line of thought would inevitably lead to the impossibility of knowing the Other, since the face (of the Other) refuses to be comprehended in the sense that the Other is irreducible to any pre-ordained sameness. How then does the self (of the actor), which is open to the imprint of the stranger, hope to negotiate with the Other who stands at the other side of the door? As an actor it was difficult for him to accept the journey towards the Other to be an essentially foreclosed one. Also, as Levinas suggests, the self not being able to face the unique difference of the Other and trying to straitjacket it with likeness of his own is a potential threat.

Chatterjee engages with this Levinasian chasm (distancing the self from the Otherin a rather paradoxical sense of the latter being enveloped with the identity of the former) in an interesting way. He wants the private self of the actor to be like a mirror, the self of which essentially involves the act of reflecting the Other.In the process, the self is put under erasure, mitigating the risk of the ‘identity of the I’ enveloping the ‘alterity of the object’.

The actor is supposed to embody the imaginaries in ways that would re-present them, on screen or stage, as closest to being real. So, it is imperative for him to inhabit and internalize the characters as much as he could. All the while it remains an encounter crisscrossed with inhabiting the imaginary and staking claims to real. Addressing this double register of performativity has nicely been explained by Chatterjee in a book-length interview:

‘The issue of realism is especially significant in acting since primarily the actor is supposed to imitate human behaviour. When I impersonate a mad, certainly I’m not going crazy myself. I’m creating an illusion of someone else – a semblance of a reality…But why am I creating illusions of reality? Simply because through that illusion I’m capturing the reality.’(Roy Choudhury, 2000:149; translation mine)

This is the pinnacle of the actorial claim: capturing the reality by creating a (believable) illusion. In other words, capturing the Other by creating a (believable) illusion of the Other. As was mentioned above, Chatterjee does not seek to reduce the Other to any comfortable semblance to his own self. Contrary to it, he prefers to be the mirror that he would be holding to the face (of the stranger) he engages with.

In that sense it is a case of one mirror reflecting another. For him, both are active mirrors in their respective ways. The actor-as-mirror reflects the Other. Simultaneously, the face of the Other is, as Chatterjee holds, another mirror that, like a microcosm, encapsulates the distinguishing features of the character. The very image of the actor holding a mirror readily brings up an iconic Shakespearean scene in which Hamlet expounds the ‘purpose of playing’ to a group of actors. While the mimetic thesis of Hamlet involves, as its basic criterion, the act of sensitizing the person/s the mirror was held up to, such an intention does not inform this specific communication of Chatterjee with the Other. Being the mirror he seeks a decentering of his own entrenched self. This is what, as he expects, would lead to a verisimilar reflection, or in other words, imitation of the Other.

Since the mirror (as in the actor) cannot look at the reflection, it devices a unique ploy to watch it: making portraits of those faces that are reflected in the actor-turned-mirror. This is where Chatterjee-the-painter informs the mimetic frame of Chatterjee-the-actor.

The mirror essentially is an empty signifier, invested with whatever that leaves its reflection on it. Being so, it requires to be stripped of everything that might threaten to foreclose the reflection. Significantly, in the interview mentioned earlier Chatterjee compared the craft of acting with a blank unwritten page, divested of prejudices and formulaic regulations. Unlike other performing arts that are heavily codified, acting as a performing art, as he explained, is essentially open, like a blank page (Roy Choudhury, 2000:145). Of course it has its basics laid out before the actor, but those are only supposed to ensure the blankness of the surface and consequently the reflection on it. Such a blank surface would tantamount the Levinasian construct of the ‘home’ that remains ‘open to the other’.

This is the ethical turn of the entire frame reinforced by the theses of both Chatterjee and Levinas, albeit in their own respective ways. Levinasian ethics, with a distinct biblical allusion, foregrounds the status of the stranger with a privilege that it shares with the poor, the widow and the orphan. Notwithstanding the ‘irreducible strangeness’, the stranger, the radically unknown, opens the door to infinity. Levinas goes to the extent of suggesting that ‘(to) be human is to be open for the unknown, for the Other, infinity, to take the risk of the unknown, which is quite opposite than to seek identity, stability, safety.’ (Saldukaityte: 2019)

Interestingly, the actorial identity, as Chatterjee asserts, is configured to be a mirror that reflects the Other. And, as has been noted earlier, the mirror cannot put a claim to a stable self. The moments of reflection require it to be radically open to what it reflects. The unknown, the Other. In the book-length interview, Chatterjee has delineated how he could retain that mirror within. It was by being open to the streams of life flowing around him. Most of them were, more often than not, radically different from the one he lived. Yet, he never ceased to be the mirror. His modest upbringing helped him to connect to the people living in vast, obscure swathes of the countryside. The mirror in him received the reflections. Also, relived it as well. As Chatterjee described the process:

‘I would rather say that the largest chunk of the Indian population is spread over the huge rural space in the country. Wherever I had the privilege of meeting those people, be it on a location or during any holiday vacation, I have never kept those rural people at bay, but have always tried to mix and chat with them. The past I have – I mean before I was taken to be a distinguished person due to my film appearances – is a lot like the lives of those ordinary, so-called anonymous people. I have never distanced myself from that self, but have nurtured it all through my life.’ (Roy Choudhury, 2000:99; translation mine)

It would be improper to locate these activities exclusively to a zone of mimetic exercise. While it evidently added to his actorial self, it has certainly gestured to an aesthetic practice informed by his exercise in ethics also. He emphasized on being ‘open-minded’, receptive enough to take the imprint of the other which, in turn, would make him a better actor. Also, a better, more sensitive human being as well. These were moments when he met the other, appreciated the layout of identity in difference and tried to organise his self – both actorial and his personal one – accordingly.

These are moments when the door was pushed. Either, as Chatterjee has described, the actor entered the strangeness of the Other. Or, the Levinasian Other made his entry into the self-as-home that remained open for it. Both would look into each other’s eyes. And, it may well lead to a moment of rupture in the self. To bring a slender hermeneutic twist to the famous Nietzschean dictum: if one gazes long into an Other, the Other will also gaze into him.

(ENDS)

Reference:

Alford CF. Levinas and Political Theory. Political Theory. 2004;32(2):146-171. doi:10.1177/0090591703254977

Chatterjee Soumitra. Atmaparichaya: Amar Bhabna Amar Smriti. Patrabharati. 2020

Levinas, Emmanuel. 2007. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated by AlphonsoLingis. Pittsburgh:Duquesne University Press.

Rockmore, Tom. Cognition: An Introduction to Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1997 1997.

http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft7d5nb4r8/

Roy Choudhury Anasua. AajKaalPorshurPrante. KrantikPrakashani. 2000 Saldukaitytė J. The Place and Face of the Stranger in Levinas. Religions. 2019; 10(2):67.

The version of the generic pronoun, when singular, has been in the masculine form. It needs to be read in gender neutral form.