Vagina Dialogues and Deborah De Robertis

Sovan Tarafder

My vagina is a shell, a tulip, and a destiny. I am arriving as I am beginning to leave. My vagina, my vagina, me.

Eve Ensler (The Vagina Workshop; The Vagina Monologues)

Those who have not yet heard of Deborah De Robertis, the (in)glorious French- Luxembourgian performance-artist and filmmaker, are quietly requested to google. Traces of the annual (and ruefully short-lived) frenzy of the International Women’s day are still there in the Gregorian almanac and what better way to celebrate the (remainder of the) month than to take a look at one of the most daring (and hence, scandalous) female bodies of the present continuous!

A timely disclaimer needs to be placed though. Confronting the body of De Robertis might well turn out to be an unsettling experience. Her denuded corporeality is the site that constantly provokes the onlooker to engage with the forbidden. Dangerously, she does not grant (the watcher/s) any escape because on camera she has the entire performance recorded. So, all sorts of responses that she finds – acceptance, avoidance and all the shades in between, turn into reactive articulation. Thus she makes engagement, on the part of her audience, simply inescapable.

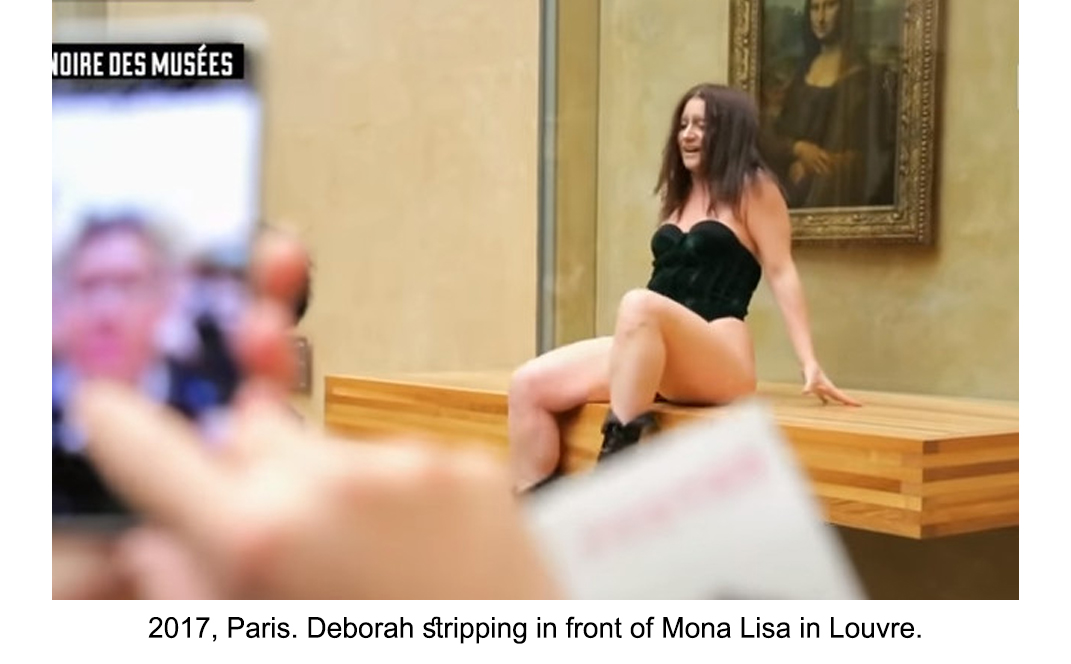

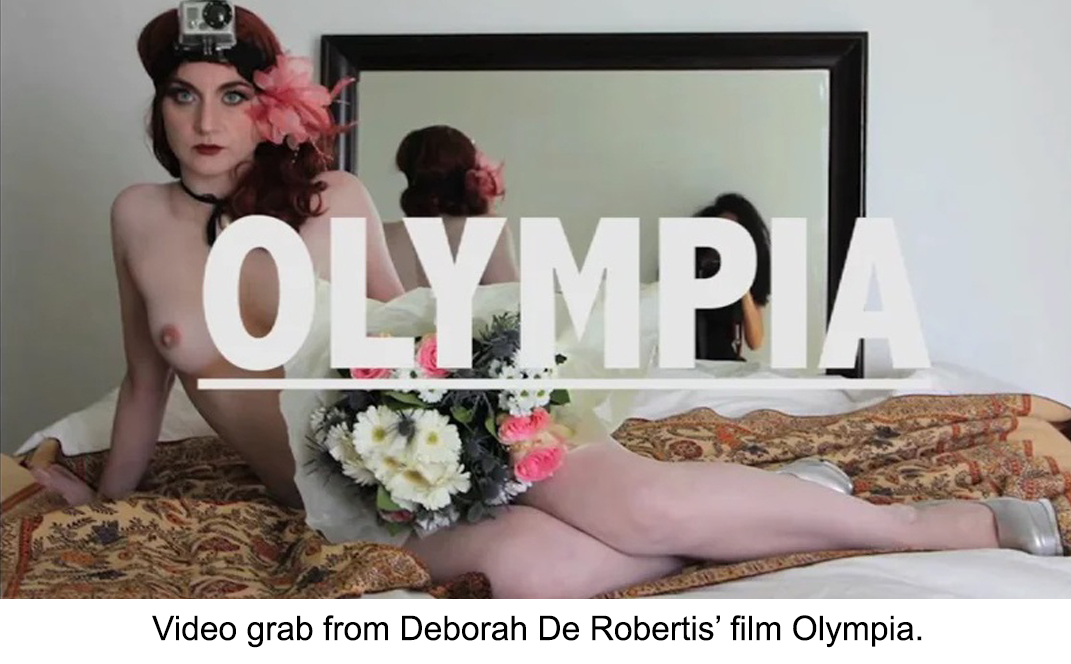

A quick look at the chronicle of dare-bare acts she (em)bodied would be engrossing. Paris 2014. De Robertis exposed her genitals at the Musée d'Orsay in front of Gustave Courbet's painting L'Origine du monde. Paris 2016. Again Musée d'Orsay found her posing nude in front of Édouard Manet's Olympia. Paris 2017. She stripped in front of the iconic Mona Lisa, her shrill cry piercing the elegant murmur of the museum, ‘My pussy my copyright!’ Paris 2018. Just when France was on boil with the yellow vest movement, she led a team of performance artists to a squadron of riot police on a Parisian street. De Robertis, along with her fellow comrades, would call themselves Marianne, the symbolic figure of the French Republic. Their bare-chested bodies covered in silver paint, five women silently faced the police, staging their performance act called Marianne is Watching You. So, for De Robertis public nudity is a tool that informs (and institutes) her agency in the act of performing the protest.

How the present essay seeks to unpack the performances of De Robertis needs to be outlined at the beginning. The basic proposition would go like this: with her performative and political nudity, the body of Deborah de Robertis is a uniquely enigmatic sentence of which she is both the subject and the object as well. While the subject (in a sentence) is the active one, considered to be the doer of the action, the object mostly gets receded to a passive mode of being, only to be acted upon as it were. This is where De Robertis intervenes by disrupting the ontological passivity of the object.

She, as the dominating subject, bares herself before an unsuspecting crowd, taking the entire congregation by utter surprise. Also, in the process she, as it appears, offers herself as an object to be recognized. The process of that recognition, interestingly, subverts the so-called passivity of the object by having camera/s placed strategically in the space De Robertis chooses to stage her performance in. The outrageously nude body of De Robertis compels people to engage with her nudity being performed. Caught at unawares, the viewer turns into the viewed object being recorded by the device/s. For the camera eye, also for the eye of the artist, even refusing to engage (with the performance) is, paradoxically enough, a sort of engagement nevertheless.

So, ‘to watch’ is a verb that Deborah De Robertis closely negotiates with in more senses than one. She watches, as the subject. She is being watched, as the object. She lets herself be watched, as the object-subject. Also, she watches that she is being watched, as the subject-object.

When she undressed in front of Manet’s Olympia, she entered into a delicately layered relation with the (painted) object in the pictorial space. At one level, she aligned herself with the portrayed model by replicating the nudity-on-display. With Olympia in tandem, exposing for De Robertis was an attempt to represent those (namely women, models and prostitutes, as De Robertis herself stated) who remain excluded (as subject to the action) but are only engaged with (as passive object to the action) by the hegemonic power in the space of art. Transgressing the visual code, De Robertis conferred the subject-status to a category of people, always already reduced to a passive and vulnerable object-status. While giving the girl in painting an explosive re-incarnation, she read aloud a letter repeatedly calling out Guy Cogeval, the director of Musée d'Orsay. In that open missive, she argued that censoring her nudity was tantamount to the straightforward denial of those persons who, unfortunately, were not granted the minimum opportunity to assert themselves (as the active subject). In that letter De Robertis categorically made her point:

"By accusing me of indecent exposure you publicly deny the point of view of the same nude models that you expose, thereby reducing them to mere objects."(King: 2017; italics mine)

Also, was it a mere happenstance that De Robertis chose Olympia to stage her protest with? The girl in the said painting stands out with her pronounced claim to subject-status. Interestingly, it was the artist, Édouard Manet himself who invested the girl (in Olympia) with a revolutionary, scandalous gaze that would directly confront the viewer. As was nicely put in a review of De Robertis’ Olympia-performance:

Olympia dares to look at us. This is the real scandal: she is looking at us. This unworthy woman, showcased only to be glared at… is looking at us. So passive, her desirable flesh ready for the taking, she should not have any agency, she should not be soliciting… And yet she dares to look at us in the eye, she dares to face us, brazenly, immodestly, defiantly. One day, maybe, we will have her, as they say, thanks to our charm –or rather our money. But we won’t own her: possessing her will be more akin to submitting to her. (Unnamed: 2016)

Clearly, the girl in the canvas breaks the normative code by refusing to be the inescapably passive object. As she throws her confrontational gaze, the viewer is likely to negotiate with it in both ways. As one being looked at (i.e. an object) and also as one looking at it from a subject position. It was Manet who decided to plot such an implosion into a seemingly innocuous painting privileging the gaze of the girl, laced with a cold, brazen defiance.

De Robertis, while investing her own nude corporeal frame with an agency of protest, sought to reprise this defiant gaze of the model. Hence, she is simultaneously the object (being looked at) and the subject that, a la Olympia, directly exchange gaze with the viewer. Also, she, as the subject, a la Manet, creates a visual field of her own. While Manet had canvas and colours at his disposal, De Robertis has herself armed with camera. She puts the onlookers and gazers into a double bind of provocation. As object (to their gaze) she incites them to engage with the sight/site of her nudity. As subject (to her action), first she makes herself a visual quote of an artwork. Then, with a headcam attached to her body as an extended limb she records the responses elicited from the audience. De Robertis, in an interview, has explained the process:

"I usually take the position of the model, but here I am both the artist and the model, or the model with the camera. The viewer thinks it is me being viewed, as a naked woman. But actually I am viewing them." (Surtees: 2016)

Simultaneously incited by the subject and the object, the watchers (curious/reluctant) get themselves embedded (as co-performers) into a performance they are watching/refusing to watch.

The way De Robertis conducts herself at the said performances comprises both verbal and non-verbal communication, the latter constituting the larger part of what she proposes to communicate. Since this essay seeks to place the arguments comparing the performativity of the artist to a linguistic schema, the activities of De Robertis would make better meaning when located within two distinct yet related processes, one propositional and another modal.

It would be good to remember here that De Robertis, in her own idiosyncratic way, relates the verbal mode with the non-verbal one when she announces that opening her legs is akin to opening her mouth. Visibly (and literally so) she foregrounds her daring vagina, letting it do the talking while her actual speech faculty comes as the supplement, as and when needed. This is how the propositional space of her performance meets its modalities. In the process the body of De Robertis begins each performance as semantically empty, only to be filled in gradually by the relational coordinates as are present on the site/s concerned.

As all performances are, hers is also one that unfolds in time. But, apart from this general procedural method, the nudity that De Robertis inflicts on her audience (both immediate and distant ones, in space as well as time) is ontologically anchored to the matrix of time. Here Giorgio Agamben in his slender treatise Nudities has thrown some light on the process:

(O)ne of the consequences of this theological nexus that closely unites nature and grace, nudity and clothing, is that nudity is not actually a state but rather an event. Inasmuch as it is the obscure presupposition of the addition of a piece of clothing or the sudden result of its removal-- an unexpected gift or an unexpected loss -- nudity belongs to time and history, not to being and form. We can therefore only experience nudity as a denudation and a baring, never as a form and a stable possession. (Agamben: 2011; 65)

As she suddenly bares herself, it is a flash that starts inscribing her semantically empty body with alphabets that undercut the patriarchal hegemony in the space of art. As the performance keeps unfolding, more reactions get recorded, the operative system of the space starts neutralising what suddenly came up as a threat (to the system). In the process what the system ends up doing is privileging the violence of her nudity. The more it guards the nude body of De Robertis, bars the watchers from reaching her, tries hard to bury the body into the web closely guarded security, the more it elevates the same to the status of a work of art, i.e. something that they are supposed to protect and not vanquish. This is the paradoxical culmination of the performance of Deborah De Robertis that the system could not properly fathom.

Giorgio Agamben, at the beginning of a chapter titled Nudity, recalls an act of performance titled VB55 by Italian artist Vanessa Beecroft. On April 8 2005 Vanessa had a huge gang of one hundred nude women (actually clothed in skin-toned nylons and slathered in almond oil) in Berlin's Neue Nationalgalerie. The women with their perfectly simulated nudity – placed almost in military formation and stark exposed to the visitors – unsettled the prospect of a hegemonic gaze of the watchers. After a certain point of time, the ‘defenceless spectators’, feeling embarrassed, started to recoil from the ‘hostile, naked bodies’ and the ‘bored and impertinent gaze’ being incessantly cast by those women.

Such a visual field, as Agamben points out, is an interesting reversal of roles as found in painting on the biblical Last Judgement.

...the girls in the pantyhose were the implacable and severe angels that the iconographic tradition always represents as being covered by long dresses. The visitors, on the other hand...personified the resurrected awaiting their judgement, whose depiction in full nudity even the most sanctimonious theological tradition has authorized (Agamben: 2011; 56)

Scattered across a few years, the moments when De Robertis stripped herself to nudity, were the moments of secret judgement when she interrogated the entire system with her aggressively naked body. It is the embodiment of transgression aimed at decentering the hegemony that covers her body. The viewers, on the contrary, are found scurrying for cover with the lid on the systematized patriarchy being off in a flash. In an interview to an eminent daily, De Robertis says something very significant:

'The exhibitionism law should not apply to my work or that of any artist or activist using nudity to say something. When we use public spaces, it is no longer private or intimate, it’s a public nudity. It becomes a uniform – like a cop.' (Surtees: 2016)

Not only does she compare her nudity with a dress (for that matter, a uniform that is a great leveller) also she likens herself to a cop, one who is supposed to hunt down the offender. Visibly, she wants to place a mirror before the system. Objectification of women and the improper/inadequate representation of women are issues that she seeks to raise her voice about. And her voice, as was noted above, lies as much in larynx as in her crotch. So, just by opening the legs, she voices something important, albeit non-verbally.

Clad in a dazzling golden dress (as bright as the frame of the original artwork), when she stretched her labia, she did make a comment on the hypocrisy of Courbet's L’Origine du monde that chose not to disturb the normative social code and stopped strategically short of portraying the innermost details of the organ that it was focussed on. Opening her vaginal passage with the painting at her back, De Robertis sought to put the image into perspective. Also, it was an attempt to reclaim her body – an attempt which she repeated, and this time verbally also – with the legendary Mona Lisa watching her from behind. Yelling ‘My Pussy My Copyright’ is the unveiling of a shimmering manifesto that nicely manoeuvres the idea of ownership informed as it is by the logo(s) of copyright. In effect, this particular announcement which seemed to have outraged the magnificent modesty of La Gioconda, serves as the microcosm of the rebellious corporeality of Deborah de Robertis.

She has a lot to ask and wants the system to answer a lot as well. Why are there so few works of women artists in the museums and galleries when the same spaces abound with works that portray women in different moods and moments of vulnerability? Why do the women need to be commoditized just in order to make the works sell? Why does the system heavily censor real life display of nudity as performance art when they, even more heavily, keep on promoting and publicizing nudity in displayed artworks just to boost the financials?

De Robertis devises some unusual ways to interrogate. Her uncovered body being the irreducible site to stage the protest, often she makes effective use of gadgets too, like when she spread open her legs placing a smartphone on the crotch with a movie running on it. There were attendants who sat below to watch the film with headphones supplying the audio feed. The performance, taking place in 2017, was called Do I have to show my pussy to show my movie? Or, in a more classical way she commented on the Christian iconography by standing nude in front of the statue of the Virgin Mary at the Catholic shrine in Lourdes, France. She just had a piece of cloth covering her head satirically mirroring the shawl of Mary.

Visibly, Deborah De Robertis has a uniquely transgressive body that lends itself to different forms of violation. It is this corporeal frame that, being the site of protest, becomes her persona in the sense Agamben would like to put it forward – a mask. Sensitizing the reader to the etymological root of the word Persona which means a mask, Agamben goes on to argue:

(I)t is through the mask that the individual acquires a role and a social identity... The struggle for recognition is, therefore, the struggle for a mask, but this mask coincides with the "personality" that society recognizes in every individual...In our culture, however, the "persona-mask" does not only have a juridical significance. It also made a decisive contribution to the formation of the moral person. (Agamben: 2011; 46-7)

Interestingly, what Agamben leads the reader to, i.e. the moral fabric, is also what constitutes the seemingly crazy but deeply ethical interventions of De Robertis. She privileges her vagina just in order to make people (and media), otherwise indifferent, start a dialogue with it. While dialogue is something usually considered to be foreclosed for that particular organ, De Robertis lets it talk and that too in a way which constructs, as Agamben puts it, a persona-mask or a personality that causes some sort of rupture unsettling the larger society and forcing them to engage with as well.

De Robertis is clear on what she seeks to do, and how. In the interview she was earlier quoted from, De Robertis reveals her modus operandi that is a fairly simple one:

"One way (to criticise the patriarchy) is to analyse and denounce stereotypes and domination. That is the way traditional feminism has worked up until now. This way contributes to making those stereotypes exist; it helps them and feeds them. The other way is to criticise domination by choosing to stand in the field of emancipation. I can walk into the Musée D’Orsay and sit down in front of L’Origine du Monde. I don’t have to ask. I do it without screaming or asking twice – I just take the position, I just do it with my body. That’s how I feel free." (Surtees: 2016)

As she takes the position, her body – unshackled and always uniquely unforeseen – would now unleash the vagina dialogues. Let the rest of the world reciprocate.

References:

Agamben Giorgio. Nudities. Stanford University Press. 2011

Surtees Joshua. 'Public nudity is a uniform': the artist who stripped off at the Musée D’Orsay.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/03/deborah-de-robertis-nudity-manet-musee-dorsay

Author unnamed: Olympia is Looking at You, or "Who’s Afraid of Deborah De Robertis?" Translation by Lucas Faugère. 7 February 2016. https://artredglasses.wordpress.com/2016/02/07/olympia-is-looking-at-you-or-whos-afraid-of-deborah-de-robertis/

King Alex. “TO OPEN MY LEGS IS TO OPEN MY MOUTH”: SEXUALITY AND ART: October 25, 2017; https://aestheticsforbirds.com/2017/10/25/to-open-my-legs-is-to-open-my-mouth-sexuality-and-art/ Also,

Andronicou Andrew. Mother of Marianne. Meet Deborah De Robertis, the creator of the powerful symbol of modern feminist France. 24 May, 2019. https://medium.com/@andronicou/mother-of-marianne-54969e51039